- Researchers say eating even when you’re full may be associated with sense of smell and behavior motivation.

- They report that food smells become less attractive when someone is full.

- If brain connection doesn’t function properly, researchers say a person’s body mass may be higher.

A group of scientists may have discovered one reason why it’s easier for some people to stop eating when they’re full and more difficult for others.

They say this may be caused by our sense of smell and neural reward systems versus negative feelings such as pain as well as the brain connection between the areas controlling those feelings.

The study from researchers at Northwestern Medicine in Illinois states their theory is based on a newly discovered structural connection between two brain regions that appear involved in regulating feeding behavior.

The researchers used neurological imaging from a large multi-center

The regions of the brain the study examined have been associated with sense of smell and behavior motivation.

The researchers found that weaker connections between these two sensory regions, the higher a person’s body mass index (BMI), the researchers said.

The areas under study connects the olfactory tubercle – part of the brain’s reward system associated with smell – and a midbrain region called the periaqueductal gray (PAG), which is involved in motivated behavior responding to negative feelings such as threat, pain and, potentially, eating suppression.

Research has shown the smell of food is appealing when a person is hungry, but the odor becomes less attractive when that person eats the food until they’re full.

The most recent study, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, reported that odors are important to guiding motivated behaviors such as eating and— in turn — olfactory perception is modulated by how hungry we are.

However, researchers haven’t fully evaluated the neural underpinnings of how the sense of smell contributes to how much we eat.

“The desire to eat is related to how appealing the smell of food is — food smells better when you are hungry than when you are full,” said Guangyu Zhou, a corresponding study author and a research assistant professor of neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, in a statement. “But if the brain circuits that help guide this behavior are disrupted, these signals may get confused, leading to food being rewarding even when you are full.”

The sensation of reward that comes with food could possibly, in turn, increase a person’s body mass index (BMI).

“And that is what we found,” Zhou said. “When the structural connection between these two brain regions is weaker, a person’s BMI is higher, on average.”

The authors hypothesized that healthy brain networks connecting reward areas with behavior areas can regulate eating behavior by sending messages indicating eating doesn’t feel good anymore once that person is full.

The researchers said that people with disrupted or weak connection circuits may not receive the stop signals and keep eating, even when they’re not hungry.

“Understanding how these basic processes work in the brain is an important prerequisite to future work that can lead to treatments for overeating,” said Christina Zelano, a senior study author and an associate professor of neurology at Feinberg, in a statement.

Zhou said they found correlations to BMI in the circuit between the olfactory tubercle and the midbrain region called the periaqueductal gray.

For the first time in humans, Zhou mapped the circuit’s strength across the olfactory tubercle, then replicated the findings in a smaller MRI brain dataset the team collected in their Northwestern lab.

“Future studies will be needed to uncover the exact mechanisms in the brain that regulate eating behavior,” Zelano said.

Emily Spurlock, a registered dietitian with the Institute for Digestive Wellbeing in New York, specializes in gut health and weight management. She also works with people who have binge eating disorder.

Spurlock, who was not involved in the research, told Medical News Today that the study offers scientific evidence that some people eat for reasons other than hunger.

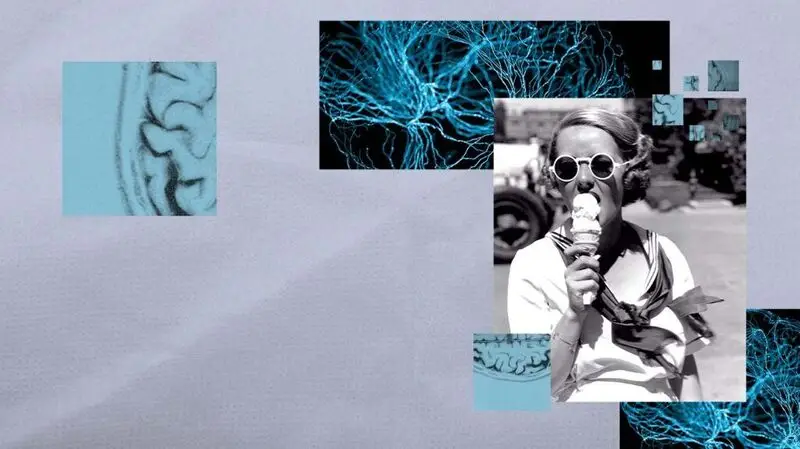

“I’ve seen this in my practice for many years. In fact, I think we all do it to some extent,” Spurlock said. “Think about Thanksgiving or any time you’ve ‘found room’ in your stomach for ice cream. Some people are better at listening to their body’s fullness signals than others. For some people, the smell and sight of a favorite dessert is more powerful than being stuffed.”

Spurlock said when a person overeats to the point of being uncomfortable the first time, they likely acknowledge it. However, the more it happens, they likely get “desensitized and overeating is no longer as uncomfortable as it was that initial time.”

“Over time, that brain connection gets ‘broken’ because it’s being ignored or overwritten by frequent overeating,” Spurlock said. “Maybe some people start off with a stronger brain connection and overeating never becomes a problem. My question from the study is if people can rebuild that connection or build a stronger connection so they are more in tune with the uncomfortable feeling of overeating?”

Kate Ringwood is the owner of Serendipity Counseling Services and a therapist specializing in eating disorders.

Ringwood, who wasn’t involved in the study, told Medical News Today that the idea of a physical connection between two brain regions that appear involved in regulating feeding behavior isn’t new. But she said she has a different perspective.

“Through my experience, those who are dieting – which often includes folks going on weight loss medications – are restricting foods,” Ringwold said. “When food is restricted, it puts the brain into ‘survival mode,’ leading your brain to think it needs to eat all the food, in fear that it will not get this food again.”

“This happens whether it is mental restricting – for example, not allowing yourself to eat cookies and then later binging when cookies are put in front of you – or physical restriction (by) simply not eating enough calories for your body to properly function,” Ringwold said. “I have seen this over and over again in the work I do with clients, leading folks to feel extremely uncomfortable and sometimes ill feeling.”

Ringwold said restricting food leads to a disconnect from one/s body.

“If you are not eating when your body is trying to signal you that it needs food, you teach your body that the signal cannot be trusted,” she explained. “This leads to distrust and confusion when it comes to hunger and fullness cues.”

Ringwold added that when someone restricts eating, their body starts shutting down hunger and fullness cues.

“The way I often phrase this to clients is, when you had to hunt for food, if your body showed signs of major hunger such as shaking, brain fog, stomach pain, you would not be able to get food,” Ringwold said. “The body is amazing in that it shuts down signals that feel ‘less important.’ When we ignore our hunger and fullness cues, it shuts them down.”