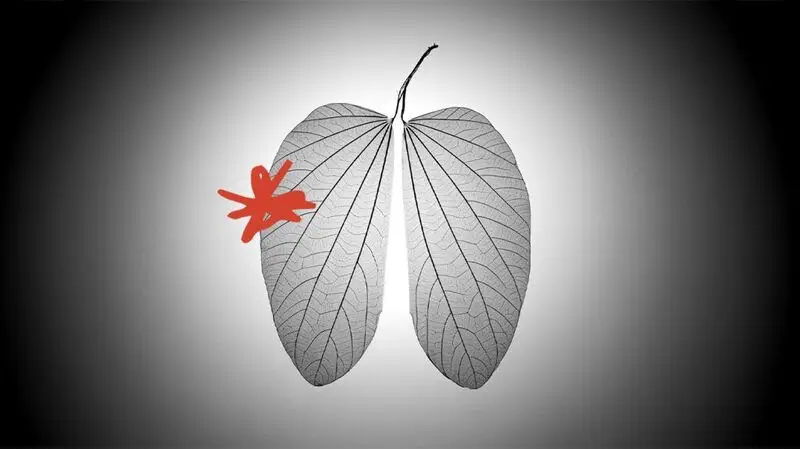

- Researchers report that people who have never smoked are less likely to respond to standard treatment for non-small cell lung cancer.

- Researchers say a combination of two genetic mutations may make cancer cells in non-smokers more resistant to treatment.

- They add that new diagnostic tests and targeted therapy are needed to address treatment-resistant cases.

Non-smokers who develop non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) can be unusually resistant to treatment for the disease.

Researchers say they think genetic mutations may be the cause.

Their

Smoking is the leading cause of lung cancer, but not all people who get lung cancer are smokers. In fact, 10% to 20% of people who get lung cancer have never smoked, according to the

The causes of lung cancer among people who have never smoked remain unclear, but experts suspect a combination of environmental, genetic, and lifestyle-related factors play a role.

Lung cancer among non-smokers is the fifth leading cause of death in the world, according to Dr. Eric Singhi, an assistant professor of thoracic head and neck medical oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

“All you need to be at risk for lung cancer is to have lungs,” Singhi, who was not involved in the study, told Medical News Today.

Targeted treatment is available for non-small cell lung cancer.

However, researchers from University College London, the Francis Crick Institute, and drugmaker AstraZeneca found that the combination of two genetic mutations may explain why standard treatment is often ineffective among non-smokers.

Targeted treatment fails in 10% to 15% patients, depending upon what kind of NCSLC is being treated, Dr. Manmeet Singh Ahluwalia of the Baptist Health Miami Cancer Institute who was not involved in the study told Medical News Today

In their new study, researchers reported that a mutation in the epidermal growth factor receptor gene (EGFR) — present in up to half of non-smokers with NCSLC — combined with a mutation in the p53 gene resulted in the development of drug-resistant tumors.

Researchers said that the only about a third of people with stage IV NSCLC and an EGFR mutation survive for up to three years.

EGFR enables cancer cells to grow more quickly, whereas the p53 gene plays a role in tumor suppression.

Typically, NSCLC is treated with drugs called EGFR inhibitors, but the study found while tumors in people with just the EGFR mutations got smaller in response to treatment, some tumors actually grew after treatment among those with both the EGFR and p53 mutations.

Lab and animal studies found that these growing, drug-resistant tumors had more cancer cells that had doubled their genome, giving them extra copies of all their chromosomes. In addition, cells with both the double mutation and double genomes were more likely to multiply into new drug-resistant cells.

“We’ve shown why having a p53 mutation is associated with worse survival in patients with non-smoking related lung cancer, which is the combination of EGFR and p53 mutations enabling genome doubling,” said Charles Swanton, PhD, a study co-author and a professor at the UCL Cancer Institute and deputy clinical director at the Francis Crick Institute, said in a statement. “This increases the risk of drug-resistant cells developing through chromosomal instability.”

“While whole genome doubling itself may not always cause cancer, it can contribute to cancer growth and disease progression in various ways,” added Singh.

Researchers noted that while non-small cell lung cancer patients are tested for EGFR and p53 mutations, there is no test currently available that can detect this dangerous genome doubling.

Work on such a test is under way, however.

“Once we can identify patients with both EGFR and p53 mutations whose tumors display whole genome doubling, we can then treat these patients in a more selective way,” said Crispin Hiley, PhD, a study co-author and an associate professor at the UCL Cancer Institute. “This might mean more intensive follow-up, early radiotherapy or ablation to target resistant tumors, or early use of combinations of EGFR inhibitors, such as (AstraZeneca’s) osimertinib, with other drugs including chemotherapy.”

“Treatment strategies such as combination therapies (targeted therapy plus another treatment) have begun to emerge, aimed at preventing the emergence of resistance to a treatment,” said Singhi.

He noted that these include using osimertinib in combination with conventional chemotherapy or amivantamab, an bispecific antibody targeting EGFR and MET, a gene that manufactures a protein involved in cellular signaling, growth, and survival.

“These trials are looking to prove whether two types of treatments together and upfront, offer better clinical outcomes for our patients than one targeted therapy alone,” he said. “A very valid concern, however, is that combination therapies tend to be more toxic for our patients, and it can be difficult to discern which patient would benefit more one therapy versus another.”

Dr. Shuresh Ramalingam, an executive director of the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University in Georgia and a non-small cell lung cancer expert who was not involved in the study, told Medical News Today that new therapies can be tailored to address NSCLC cases where EGFR inhibitors are ineffective.

“When targeted treatments stop working, it is not uncommon for physicians to conduct molecular testing to determine if there are new mutations in the tumor,” said Ramalingam, who is currently working on a new intervention for treating Stage III NSCLC tumors that cannot be removed surgically. “This knowledge informs appropriate interventions that could overcome the resistance mechanism. For example, for patients with EGFR mutation, a known resistance mechanism with targeted therapy is a new mutation known as the C797S mutation. There are new experimental drugs that are capable of overcoming this specific resistance mechanism in clinical trials.”

The proportion of lung cancers occurring in individuals who have never smoked has increased in the past several decades, particularly among women and in younger age groups, said Ahluwalia.

“Approximately two-thirds of [these] cases occur in women, making women who have not smoked more than twice as likely to develop lung cancer than men who have not smoked,” he said.