- As human beings get older, our movements naturally start to slow down.

- New research suggests that older adults may move slower partly because it costs them more energy than younger adults.

- Scientists believe these findings could lead to new diagnostic tools for diseases such as Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis.

It’s common knowledge that our bodies naturally become slower in their movements

Some potential explanations could include a slower metabolism,

Now, researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder say older adults may move slower partially because it costs them more energy to do so than younger adults.

Scientists believe this new research — recently published in the journal The Journal of Neuroscience — may help lead to new diagnostic tools for diseases such as Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis.

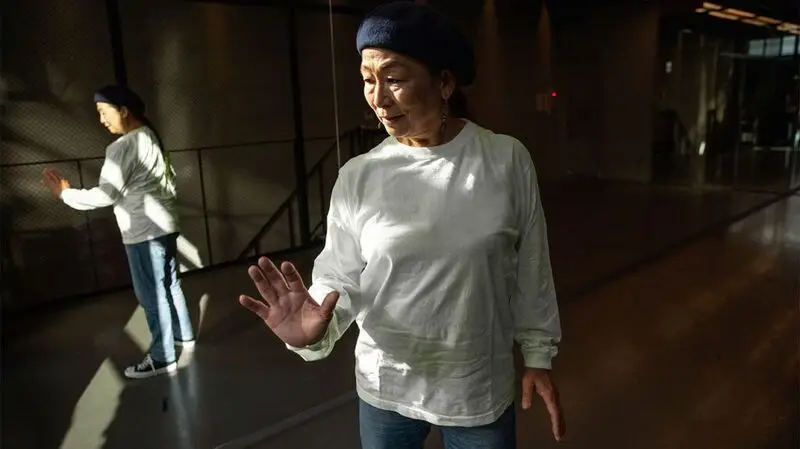

For this study, researchers recruited 84 healthy participants, including younger adults ages 18 to 35 and older adults ages 66 to 87.

During the study, participants were asked to reach for a target on a screen holding a robotic arm in their right hand. The robotic arm operated similarly to a computer mouse.

Through analyzing the patterns of how study participants performed their reaches, scientists found that older adults modified their movements at certain times to help conserve their more limited amounts of energy, compared to younger adults.

“With age, our muscle cells may become less efficient in transforming energy into muscle force and ultimately movement,” Alaa A. Ahmed, PhD, professor in the Paul M. Rady Department of Mechanical Engineering in the College of Engineering and Applied Science at the University of Colorado Boulder and senior author of this study explained to Medical News Today.

“We also become less efficient in our movement strategies, possibly to compensate for lower strength. So we recruit more muscles, which costs more energy, to perform the same tasks.”

Ahmed and her team also wanted to see how aging might affect the “

Once again, participants were asked to use the robotic arm to operate a cursor on a computer screen. The objective was to reach a specific target on the screen. If they hit the target, participants were rewarded with a “bing” sound.

Researchers found both young and older adults arrived at the targets quicker when they knew they would hear the “bing.”

However, scientists say they achieved this differently — younger adults just moved their arms faster while older adults improved their reaction times, starting their reach with the robotic arm about 17 milliseconds sooner on average.

“The fact that the older adults in our study still responded to reward by initiating their movements faster tells us that the reward circuitry is to some extent preserved with age, at least in our sample of older adults. However, there is evidence from other studies that reward sensitivity is reduced with increasing age. What the results do tell us is that while older adults were still similarly sensitive to reward as young adults, they were much more sensitive to effort costs than younger adults, so age seems to have a stronger effect on sensitivity to effort than sensitivity to reward.”

— Alaa A. Ahmed, PhD, senior study author

Researchers believe their findings may help lead to new diagnostic tools for

“Movement slowing as we age can significantly impact our quality of life,” Ahmed explained.

“It can restrict not only physical but social activities. It’s important to understand the underlying causes and determine if there are potential interventions that can help slow or eliminate the decline.”

“Additionally, slowing of movement not only occurs with age but is a symptom of a number of

“Why is this? Why do disorders, such as depression, which are associated with reward circuitry in the brain, also lead to a general slowing of movement? For me, this suggests that movement speed is telling us about a lot more than just movement-related brain circuits and muscles.”

“A better understanding of why movement is slowing in these various disorders can provide more information about the underlying causes, which can help identify better interventions. An advantage of using movement as a biomarker is that it is an easily accessible and noninvasive measure. So tracking someone’s movements either in the lab or throughout their daily activities may at some point provide a valuable biomarker of neurological health.”

—Alaa A. Ahmed, PhD, senior study author

After reviewing this study, Clifford Segil, DO, a neurologist at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, CA, told MNT that he agrees with this study’s encouragement of exercise as we age, even if it takes more energy to produce the same activity done as a young person.

“My dictum treating my elderly patients as a neurologist is ‘If you don’t use it you will lose it!’” Segil continued. “I agree encouraging elderly patients to move has multiple Health benefits in agreement with this paper’s authors.”

“I would like to see a concomitant EEG (electroencephalogram) running on these study participants to determine if their brain activity does slow down or increase during these activities to support the author’s claims,” he added.

“I think more research on how an elderly brain adapts to the challenges of aging and moving would be fascinating to read and helpful to my aging patients.”

MNT also spoke with Ryan Glatt, CPT, NBC-HWC, senior brain Health coach and director of the FitBrain Program at Pacific Neuroscience Institute in Santa Monica, CA, about this study.

“(This) study on why older adults move slower offers an intriguing hypothesis linking slower movements to energy conservation and reward processing,” Glatt said.

“However, the conceptual leap from observed behavior to underlying neural mechanisms requires cautious interpretation. Without direct neurological evidence correlating movement patterns with brain function changes due to aging, the conclusions remain speculative.”

“To strengthen the findings, future research should aim to directly link the behavioral data with neurophysiological evidence. Employing a broader methodological approach, including longitudinal studies and diverse population samples, could help delineate how universally these proposed mechanisms apply across different aging trajectories. Additionally, replicating the study with a larger sample size and varying conditions would be crucial to verify the robustness and generalizability of the initial result.”

— Ryan Glatt, brain health coach