- Being consistently lonely over a long period of time significantly increases one’s risk of having a stroke, finds a new study.

- Loneliness may increase the risk of strokes through three general pathways: physiological, behavioral, and psychosocial.

- There are many reasons people may be lonely, some of which are internal and some of which originate externally.

- Working with a healthcare professional may provide tools for addressing loneliness.

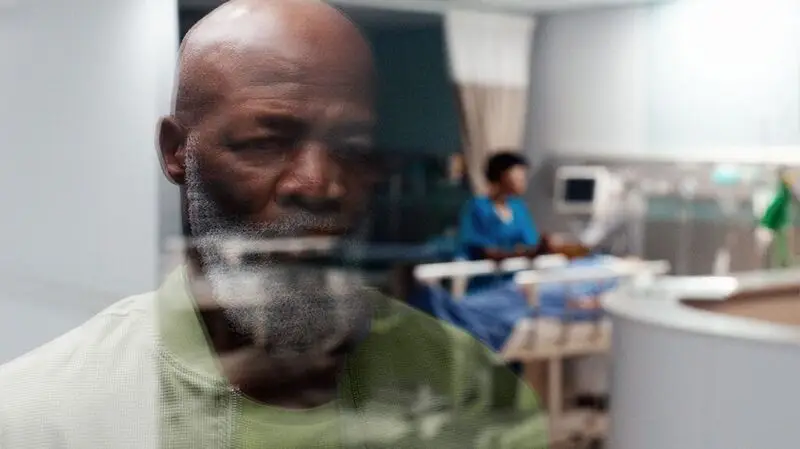

A new study finds an increased risk of stroke among people who report themselves as being lonely over the long term.

Participants in the study who reported feeling lonely at two interviews four years apart were found to be at a 56% higher risk of stroke.

The study offers a unique perspective derived from interviewing participants twice to gauge the effect of chronic loneliness. Previous research has questioned individuals only at a single time, and thus did not track loneliness’ long-term effects.

The researchers analyzed data from the Health and Retirement Study conducted from 2006 to 2018. Only participants with two recorded measurements of loneliness were included in the new study.

The study’s 8,936 participants were aged 50 and older and had never had a stroke. Their loneliness was measured according to their responses to questions in the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale.

Participants were categorized as:

- Consistently high — people who score high during both assessments

- Consistently low — people with low levels of loneliness in both assessments

- Remitting — people with a high loneliness score at the first measurement, but not at the second

- Recent onset — people with a low loneliness score at the first measurement but who had a high loneliness score at the second.

The new study found that remitting and recent participants were 25% more likely to have a stroke. People with low loneliness scores were found to be at no increased risk.

The study is published in

The study’s corresponding author, Yenee Soh, ScD, research associate of social and behavioral sciences at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, MA, explained what may lie behind the connection.

While noting that defining the mechanism linking loneliness to stroke was beyond the scope of the study, Soh said, “Based on the literature, there are three broad pathways that generally describe how loneliness can impact stroke risk: physiological, behavioral, and psychosocial.”

Previous research has suggested that possible physiological mechanisms include inflammation, reduced immunity, and increased hypothalamic pituitary-adrenocortical activity.

Jayne Morgan, MD, cardiologist and the executive director of health and community education at the Piedmont Healthcare Corporation in Atlanta, GA, who was not involved in the study, added elevated blood pressure due to mental health stressors to that list.

“Further,” Morgan said, “self-abusive behaviors such as decreased physical activity, overeating, high consumption of ultraprocessed foods, increased alcohol intake, increased use of cigarettes and/or drugs, decreased compliance with prescribed medications, and poor sleep hygiene may all be factors.”

A psychosocial influence may lie in a person’s inability to “maintain satisfying social relationships, which may result in longer-term interpersonal difficulties that in turn may affect stroke risk,” she said.

“I think the key point is that it’s not just loneliness that likely contributes to the risk of stroke. It’s a combination of factors. The fact that you’re lonely most likely means that you’re less able to care for yourself,” said Yu-Ming Ni, MD, board certified cardiologist and lipidologist at MemorialCare Heart and Vascular Institute at Orange Coast Medical Center in Fountain Valley, CA, who was also not involved in the study.

“Loneliness is actually the painful feeling of being alone,” noted Morgan.

“Interestingly, people who are isolated may not actually feel lonely, and those who are lonely may actually be surrounded by tons of people,” Morgan pointed out. The study, in fact, separates loneliness from social isolation.

You may be “feeling as if you are standing on the sidelines, feeling misunderstood, disconnected with the group, as opposed to people who are isolated who are actually physically separated and have very few social/human interactions,” she said.

The age group most at risk for loneliness is actually young people 18 to 22 years of age, said Morgan — they are also at the highest risk of social isolation, anxiety, and depression.

Nonetheless, pointed out Soh, “As the population ages, this is an increasing concern for both the aged, and the young.”

Complementing the study’s conclusion that long-term loneliness poses the highest risk of stroke, the USPTF (United States Preventive Task Force) recommends doctors evaluate patients for depression, loneliness, and isolation.

“We may be moving into an era where doctors begin to prescribe social interaction and provide referrals to community resources,” hoped Morgan.

For some, loneliness may not be a problem, Ni said. “You can choose to be lonely because that’s what gives you strength, that’s what is important for you, and meaningful for you. Plenty of people live their lives this way, very functionally, very effectively, and are able to take care of themselves well enough to not develop a stroke,” contended Ni.

At the same time, loneliness may be a product of external forces, such as social challenges based on ethnicity, race, socioeconomic status, or location.

“It remains inconclusive whether behavioral or therapeutic interventions would reduce loneliness. That said, this issue should not only be tackled at the individual level and/or in a healthcare setting,” said Soh.

“We also need to understand whether there are structural and societal factors that contribute to loneliness and work collectively as a society to address loneliness. There are also an increasingly wide range of organizations and initiatives that provide resources to help combat loneliness, which may be helpful to follow.”

— Yenee Soh, ScD