When stool (feces) leaks out from the rectum accidentally, it is known as fecal incontinence. Under normal circumstances, stool enters the end portion of the large intestine, called the rectum, where it is temporarily stored until a bowel movement occurs. As the rectum fills with stool, the anal sphincter muscle (a circular muscle surrounding the anal canal) prevents feces from coming out of the rectum until it is time to have a deliberate (controlled) bowel movement.

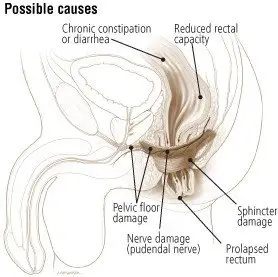

Various conditions can cause incontinence. The most common reason for incontinence is that the anal sphincter becomes too weak to hold the stool in the rectum. Alternatively, sometimes the rectum may start to lose its capacity to store the stool, or the person may be unable to feel that the rectum is full. Also, a person must be able to be aware of the need to empty the bowel, and be mobile enough to reach the bathroom in time. Diarrhea from any cause makes incontinence worse (since it is more difficult to control liquid stool than solid stool).

The anal sphincter may become weak either from direct damage to the muscle or from damage to the nerves that cause the muscle to contract normally.

Damage to muscles can be caused by:

- Childbirth

- Rectal surgery

- Inflammatory bowel disease (especially Crohn's disease)

- Trauma

- Damage to nerves can be caused by:

- Diabetes

- Spinal cord injury

- Multiple sclerosis

- Unknown factors

Sometimes the sphincter muscle may be weak simply from aging, since all our body muscles tend to weaken as we grow older.

Symptoms

Symptoms of fecal incontinence can range from intermittent mild spotting of liquid stool, to the complete inability to contain solid stool.

Diagnosis

Like any other anal or rectal condition, physicians evaluate incontinence initially by inspecting the anal area, feeling inside the anus with a gloved finger (digital rectal exam), and looking inside the anal canal with a small short scope ("anoscope"). If there has been damage to the sphincter muscle, there may be a visible defect or scarring in the anal canal.

Also, the digital rectal exam may reveal a weakness of the sphincter muscle. Nerve damage might be identified with the "wink" test, in which the doctor touches the anus to see if the sphincter contracts normally.

The next test is often a sigmoidoscopy. A doctor inserts a thin, flexible tube (fitted with a light and video camera) into the rectum to look for inflammation, tumors or other problems. Your doctor may also suggest a barium enema x-ray or colonoscopy to look for problems in the colon further upstream.

Further diagnostic tests may include anal manometry, electromyography ("EMG"), and anal ultrasound. Anal manometry, measures the strength of the anal sphincter muscle. EMG measures the function of the nerves that go to the sphincter muscle. Anal ultrasound can give a picture of the structure of the muscle (to see if there are any tears or defects in muscle).

Expected Duration

Fecal incontinence, when due to a temporary problem such as severe diarrhea or fecal impaction, disappears when that problem is treated. However, in some cases fecal incontinence can be severe and very difficult to control. This is more likely to occur in people who are elderly, frail or immobile.

Prevention

Most often fecal incontinence cannot be prevented. However, taking steps to have regular bowel movements and avoiding constipation with fecal impaction can help.

Treatment

Treatment for fecal incontinence depends on the cause of the problem. If fecal incontinence is the result of diarrhea, fiber supplements that contain psyllium may help you to have firmer stools, which increase the sensation of rectal fullness. Anti-diarrhea medications such as "Kaopectate," loperamide ("Imodium") or "Lomotil" are other options for treating diarrhea.

If the condition is the result of impaction, the hardened stool can be removed by hand or with enemas. Emptying the rectum completely each morning (sometimes with the aid of a glycerin suppository or an enema) may help, since there will be less stool to leak out during the day.

Pelvic muscle exercises (Kegel exercises) are sometimes useful. You need to practice contracting your sphincter at least three times a day. It is also crucial that you contract your anal muscles whenever you feel fullness in the rectum.

Sometimes an effective way to treat chronic fecal incontinence is with biofeedback. People can learn, with the help of a monitor and a nurse, to coordinate contraction of the sphincter muscle with the fullness that occurs when stool is in the rectum. Learning the technique requires patience and practice.

When conservative treatments fail, the final option is surgery. Some people benefit from operations to surgically repair the anal sphincter muscle ("sphincteroplasty"). Sphincteroplasty is effective only if tests show that there has been major damage to the muscle from childbirth, trauma, or previous surgery (it is not effective if the sphincter muscle is weak just from nerve damage or aging).

Another option is to implant electrical stimulation electrodes over the tailbone to help contract the sphincter muscle ("sacral nerve stimulation"). Artificial anal sphincter devices are available, but they have substantial complication rates. All of these procedures have only moderate success rates, however.

Finally, if all else fails, surgery to create a colostomy can improve the quality of life for some patients with severe incontinence.

Treatment options

The following list of medications are in some way related to or used in the treatment of this condition.

- dextranomer/sodium hyaluronate

When to Call a Professional

Because of the embarrassment surrounding fecal incontinence, many people wait longer than necessary before seeking medical help. If the inability to control your bowel movements is an ongoing problem, consult your doctor.

Prognosis

Although some types of fecal incontinence are harder to treat than others, most people with this problem can achieve some improvement. Between 70% and 80% of people with this problem get at least some relief with treatment.

Additional Information:

American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)

http://www.familydoctor.org/

American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons

http://www.fascrs.org

National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

https://www.niddk.nih.gov/